The Unexpected Mother

By Arpita Rathi

Poised to impose a blanket ban on commercial surrogacy, the Indian Government proposed and consequently passed the Surrogacy Bill in June, 2020. Surrogacy, another word for ‘substitution’, is the practice of a woman carrying a child for someone else. The bill aims to eliminate exploitation in the commercial surrogacy business and imposes stringent rules for surrogate mothers, genetic parents, medical professionals and other stakeholders involved. However, it becomes essential to understand the far-reaching impact of the bill. Can the bill fulfill its said objective and if yes, to what extent?

A Booming Industry

Surrogacy has always been a part of history as for many years women have nominated other women to give birth on their behalf. However, in recent years, there has been a boom in the surrogacy industry with technological advances such as In-Vitro Fertilisation (IVF) as well as softening of cultural attitudes, making it a global phenomenon. The surrogacy industry has also been influenced by the rise of global ‘health tourism’ wherein people travel to other countries where specific medical procedures are legal or unregulated.

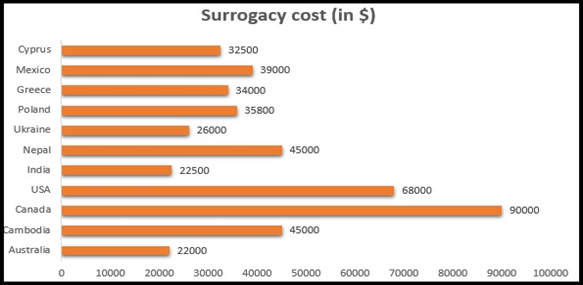

The Confederation of Indian Industry estimated commercial surrogacy to be a $2 billion industry by 2012, and the Indian Council of Medical Research, before recent regulations, expected these numbers to rise to $6 billion by 2018.With soaring demand for surrogates all over the world, the price going up is not a surprise. India, with an estimated 12,000 foreigners visiting each year to hire a commercial surrogate, is one of the top surrogacy destinations. India not only has a high proportion of skilled doctors but also a large population of women for this purpose, with the estimated cost of commercial surrogacy as low as $10,000, a fraction of the cost in the US which is about $100,000. As Sally Rhoads-Heinrich, a surrogacy consultant and owner of Surrogacy Canada Online, put it, “India had the perfect opportunity to make an amazing surrogacy system.”

Rationale of the Bill

In India, the entire process is facilitated by third-party clinics and consultants who match parents with these surrogates. The combination of profit-driven clinics and financially desperate surrogates has led to serious concerns about the ethics of surrogacy in India. The bill, thus, primarily aims at regulating the surrogacy industry.

- A major concern is the health risk for surrogates due to the way clinics and fertility experts flout the essential guidelines given to them. For instance, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) guidelines state that surrogates can be implanted with a maximum of three embryos. However, many clinics plant more than they should, increasing the risk of multiple births, which have substantial health risks.

- The total lack of autonomy that surrogates face during the entire process is also alarming. A surrogate mother is the lowest rung in the surrogacy chain and remains the most vulnerable. Usually unaware of the existing legal as well as medical rights, she is left at the mercy of agents and is not able to negotiate her own terms of the contract. These surrogates are forced to live in cramped fertility clinics with their every movement being monitored. Moreover, numerous horrific documentations of women being forced into complications or, in some cases, even death have come up.

- There have also been concerns that commercial surrogacy can lead to ‘trafficking of children’.

Therefore, the bill is meant to restore the dignity of the stakeholders and eliminate such inhumane practices. However, even though the bill has a promising objective, a deeper understanding of the implications of some of its provisions might help to see what the impact of the bill may be.

Issues with the Bill

- Exploitation may Still remain

The Health Minister of India advocated that such a ban will encourage people to adopt alternative methods such as adoption. However, it disregards the fact that the compulsion and want to have a biological child is not going to go away. On the other hand, it might encourage illegal means to complete the same process. This argument is based on evidence that shows that when practices with high demand, such as sex work or illicit drugs, are made illegal, they go underground. And when things move into unregulated environments, they are at higher risk of being exploitative.

Moreover, altruistic surrogacy – a form of surrogacy where the surrogate does not receive monetary compensation and is usually in close relation to the intended parent, as proposed by the bill, can also give results that are not so fruitful. Situations where decisions are being taken under family pressure might unfold where people are demanded to go through mentally, cognitively and physically demanding labour and that too, for no compensation whatsoever. Surrogacy consultant, Rhoads-Heinrich points to the Canadian context, saying she finds altruistic surrogacy “exploitative”. Moreover, in the altruistic arrangement, the commissioning couple gets a child; and doctors, lawyers and hospitals get paid. So why are surrogate mothers expected to practice altruism without a single penny?

- Extinguishing a form of employment

A feminist argument against the ban is that the policy is paternalistic in nature and restricts the choice of employment for a woman whose choices are already limited. Moreover, a large proportion of women turn to surrogacy as a viable employment option as a way out of abject poverty. Banning it will take away their agency of choice and right to choose their own forms of employment.

- Lack of inclusivity

The bill proposes surrogacy with a rather strict set of restrictions such as only heterosexual Indian couples who are within a specific age range, have been married for at least five years and who have no children, are eligible. This excludes foreign, homosexual, unmarried couples and single intending parents. No reason is provided why only married couples are being allowed to enter into surrogacy, while the same benefit is being denied to same-sex couples or people with no romantic partner. It seems to resort to a regressive view that only heterosexual couples are entitled to have a biological child.

More than a ban, the need of the hour is to regularise the surrogacy industry in India so that the surrogate mothers are recognized as workers with proper legal rights and minimum compensation levels. As Bronwyn Parry, Professor of Social Science, Health and Medicine and Head of the School of Global Affairs at King’s College London in England says, “I think it’s a practice that ought to be centrally organized.” Only if it is recognised as labour and is helped with the protection of rights, surrogacy laws will have the power to empower women in our country.