The Theatrics of a Good Deal: Psychological Pricing and Mental Accounting

By Suhani Jain

Basic. Standard. Premium.

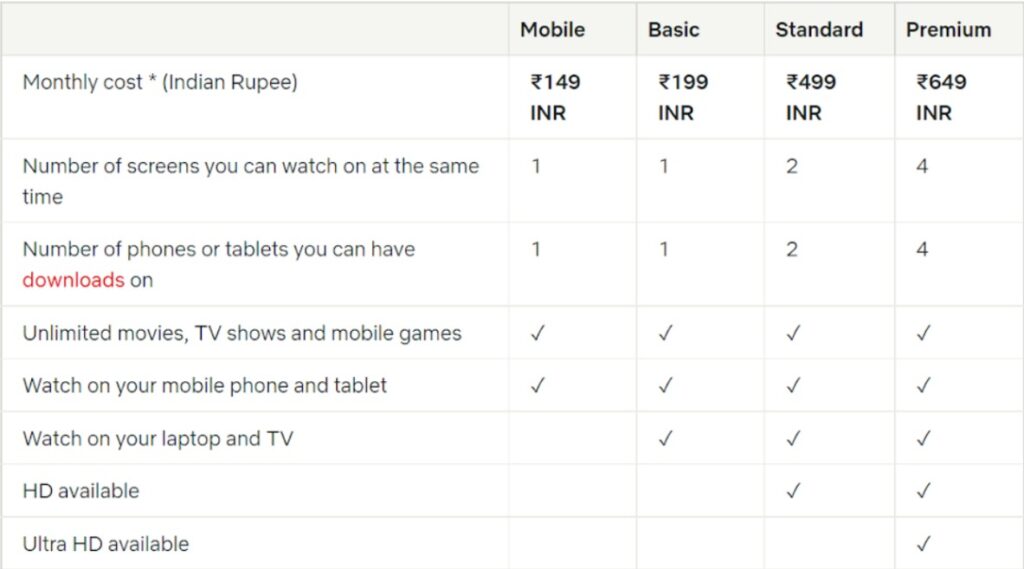

Glaring at my laptop screen, I browsed through Netflix’s pricing and plans as I attempted to carefully choose a plan that sat ‘just right’ for me…and my friends (read: parasites) using my account. The Basic Plan, while extremely affordable, seemed subpar- only offering a single screen viewing option. Conversely, the Premium Plan seemed fairly appealing but somehow overpriced. As a result, the only viable, ‘compromise option’ became the Standard Plan.

Little did I know, at that moment, I had fallen prey to what is called the Goldilocks Effect. In the children’s fairytale, Goldilocks has to choose the appropriate porridge from the three in front of her, to satiate her hunger adequately. Following trial and error, she finds the porridge which is neither too hot, nor too cold, and is ‘just right’. Akin to Goldilocks, humans also look for seemingly ‘rational’ options that fit their needs, wants and capabilities the best. Alongside, they possess a strong tendency to avoid extreme options.

Leveraging this very psychology, Multinational Corporations such as Netflix, price their subscription models in a way that most people feel persuaded to buy the Standard Plan. Had Netflix only offered two plans- Basic and Premium- most viewers would have picked the former, consequently lowering revenue generation per customer. Using this ‘Three-Tier Pricing’ technique, brands are able to create the facade of a ‘good deal’- the Standard Plan in this case- convincing the consumer that they have avoided extremity and made a ‘rational’ choice.

Furthermore, the three Netflix laptop subscription plans in India are priced at ₹199, ₹499 and ₹649 respectively. If one notices carefully, all these end with ₹9. This practice of pricing products slightly lower than a whole number is widely used by companies and is termed ‘psychological pricing’. Such prices create an illusion in the mind of the customers, bringing the perceptual flaw called the left digit effect into play. From empirical evidence, humans have been observed to pay a disproportionate amount of attention to the digit on the left (1 in ₹199). The customer does not round up the price, making them perceive the value of the package to be closer to ₹100 than ₹200, even though ₹199 is only a rupee shy of the latter. According to a study on ‘Heuristic Thinking and Limited Attention in the Car Market’, cars which had odometer readings of 79,999 miles are sold for roughly $210 more as compared to cars with odometer readings of 80,000 miles.

So what does this mean?

All of this points towards one direction- consumers’ idea of a ‘good deal’ is very subjective to the situation. Drinks at a movie theatre or an amusement park are priced much higher than they would be at a convenience store, yet we seem to buy them. The answer to this puzzle is rooted in transaction utility- the merit of the transaction itself. Our understanding of a ‘reasonable’ price is dynamic and flexible, and the transaction utility can alter our judgement drastically. Transaction utility is also a key cause of a much larger behavioural bias, called Mental Accounting. As per this bias, humans tend to attach different values to the same amount of money, depending on factors such as how that amount was earned, how they intend to use it, and how it makes them feel. While money has an objective and consistent value, i.e. ₹2000 earned as salary or won at a casino has the same monetary value, we do not think of this amount in absolute terms. This violates the fundamental property of money- its fungibility. Money is fungible, for a ₹2000 note has the same value whether it came from a casino or as salary. Despite that, a person is more likely to spend the money won at a casino on ‘luxury’ items which they would not have accommodated in their budget, and would not spend their routine salary on. We assign certain differential labels to money, and thus allow multi-million corporations to use this psychology to trick us into believing we’ve copped great deals. Even at restaurants, the prices on the menu cards are usually written in a smaller font, and generally do not have the currency sign beside them. Removing the currency sign drives the customer’s attention away from the fact that they’d be spending their hard-earned money, and smaller fonts further exacerbate this.

Big companies have used these pricing tactics on consumers from time immemorial, further strengthening Kahneman, Tversky and Thaler’s claims about the consumer not being truly ‘rational’. Mental accounting alters our perception of our own finances, and can even be a barrier to saving or paying bills on time. So, the next time you’re about to go above your budget at a store, stop and think. For all those products in your cart, do you think you’re getting a good deal?

Citations:

- Wagner, U., & Jamsawang, J. (2012). Several Aspects of Psychological Pricing: Empirical Evidence from some Austrian Retailers. European Retail Research, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8349-7144-9_1

- Here’s What You Need to Know About Psychological Pricing (Plus 3 Strategies to Help You Succeed). (2020, August 7). Omnia Retail. https://www.omniaretail.com/blog/heres-what-you-need-to-know-about-psychological-pricing-plus-3-strategies-to-help-you-succeed

- The Decision Lab. (2021, September 30). Mental Accounting – Biases & Heuristics. https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/mental-accounting/

- Yu, E. (2021, June 28). Psychological Pricing: 4 Strategies, Examples, Tactics. ProfitWell. https://www.priceintelligently.com/blog/bid/181764/psychological-pricing-strategy-where-s-your-head-at